Surprise Inflation Can Help People Who Borrow Money.

Inflation and Debt

For several years, a heated debate has raged amidst economists and policymakers about whether nosotros face a serious risk of aggrandizement. That debate has focused largely on the Federal Reserve — particularly on whether the Fed has been too aggressive in increasing the coin supply, whether it has kept interest rates too low, and whether information technology tin exist relied on to reverse course if signs of inflation sally.

But these questions miss a grave danger. Every bit a result of the federal government's enormous debt and deficits, substantial inflation could break out in America in the side by side few years. If people become convinced that our government will stop upwards printing money to comprehend intractable deficits, they volition see inflation in the future and then will try to get rid of dollars today — driving upwards the prices of goods, services, and eventually wages beyond the entire economy. This would amount to a "run" on the dollar. As with a bank run, nosotros would not be able to tell ahead of time when such an consequence would occur. But our economy will be primed for it as long as our fiscal trajectory is unsustainable.

Needless to say, such a run would unleash fiscal anarchy and renewed recession. Information technology would yield stagflation, not the inflation-fueled boomlet that some economists hope for. And there would be substantially nothing the Federal Reserve could do to finish information technology.

This concern, detailed below, is hardly conventional wisdom. Many economists and commentators do not recollect it makes sense to worry about inflation right now. Later all, inflation declined during the fiscal crisis and subsequent recession, and remains depression by mail service-war standards. The yields on long-term Treasury bonds, which should rise when investors encounter inflation ahead, are at half-century low points. And the Federal Reserve tells us not to worry: For example, in a statement concluding August, the Federal Open Market Commission noted that "measures of underlying inflation have trended lower in contempo quarters and, with substantial resources slack continuing to restrain cost pressures and longer-term inflation expectations stable, aggrandizement is likely to be subdued for some time."

Simply the Fed's view that inflation happens only during booms is too narrow, based on simply i interpretation of America's infrequent post-state of war experience. It overlooks, for example, the stagflation of the 1970s, when inflation broke out despite "resource slack" and the apparent "stability" of expectations. In 1977, the economy was also recovering from a recession, and inflation had fallen from 12% to 5% in just two years. The Fed expected further moderation, and surveys and long-term interest rates did not point to expectations of college inflation. The unemployment rate had slowly declined from nine% to 7%, so as now the conventional wisdom said it could be further lowered through more "stimulus." By 1980, notwithstanding, inflation had climbed back upwardly to 14.v% while unemployment also rose, peaking at 11%.

Over the broad sweep of history, serious inflation is most often the fourth horseman of an economic apocalypse, accompanying stagnation, unemployment, and financial chaos. Think of Zimbabwe in 2008, Argentina in 1990, or Deutschland after the world wars.

The primal reason serious inflation frequently accompanies serious economic difficulties is straightforward: Inflation is a form of sovereign default. Paying off bonds with currency that is worth half as much equally it used to be is similar defaulting on half of the debt. And sovereign default happens not in boom times but when economies and governments are in trouble.

Most analysts today — even those who practise worry about inflation — ignore the direct link between debt, looming deficits, and inflation. "Monetarists" focus on the ties betwixt inflation and coin, and therefore worry that the Fed'southward contempo massive increases in the money supply will unleash similarly massive aggrandizement. The views of the Fed itself are largely "Keynesian," focusing on interest rates and the aforementioned "slack" as the drivers of inflation or deflation. The Fed's inflation "hawks" worry that the cardinal bank will go along interest rates too low for too long and that, once inflation breaks out, information technology will be hard to tame. Fed "doves," meanwhile, think that the central banking company tin can and volition enhance rates rapidly plenty should inflation occur, so that no i need worry nigh aggrandizement now.

All sides of the conventional inflation argue believe that the Fed can end any inflation that breaks out. The merely question in their minds is whether it actually will — or whether the fear of higher interest rates, unemployment, and political backlash will lead the Fed to let aggrandizement leave of control. They assume that the authorities will e'er have the fiscal resources to back up any monetary policy — to, for example, consequence bonds backed past taxation revenues that tin can soak upward any excess money in the economic system. This assumption is explicit in today's bookish theories.

While the supposition of financial solvency may have made sense in America during nearly of the post-state of war era, the size of the authorities'due south debt and unsustainable future deficits now puts us in an unfamiliar danger zone — one beyond the realm of conventional American macroeconomic ideas. And serious aggrandizement often comes when events overwhelm ideas — when factors that economists and policymakers practice not sympathize or have forgotten well-nigh suddenly emerge. That is the risk we face up today. To properly understand that risk, we must first understand the ideas underlying our debates almost inflation.

THE KEYNESIANS' CONFIDENCE

The Federal Reserve, and about academic economists who opine on policy, have an essentially Keynesian mindset. In this view, the Fed manages monetary policy by changing overnight interbank involvement rates. These rates bear upon long-term interest rates, and so mortgage, loan, and other rates faced past consumers and business borrowers. Lower interest rates drive higher "demand," and higher need reduces "slack" in markets. Eventually these "tighter" markets put upward pressure level on prices and wages, increasing inflation. Higher rates have the contrary effect.

The Fed's mission is to command interest rates to provide just the correct level of demand so that the economy does non grow likewise speedily and cause excessive inflation, and too so that it does not grow too slowly and sink into recession. Other "shocks" — similar changes in oil prices or natural disasters that affect supply or demand — can influence the "tightness" or "slack" in markets, so the Fed has to monitor these and artfully offset them. For this reason, most Fed reports and Open Market Committee statements showtime with lengthy descriptions of trends in the real economy. It'south a tough task: Even Soviet fundamental planners, who could never quite go the toll of java right, did not confront so daunting a job every bit finding merely the "right" interest rate for a circuitous and dynamic economy like ours.

The Fed describes its recent "unconventional" policy moves using this same general framework. For instance, the recent "quantitative easing" in which the Fed bought long-term bonds was described as an culling manner to bring down long-term interest rates, given that short-term rates could non go downwards farther.

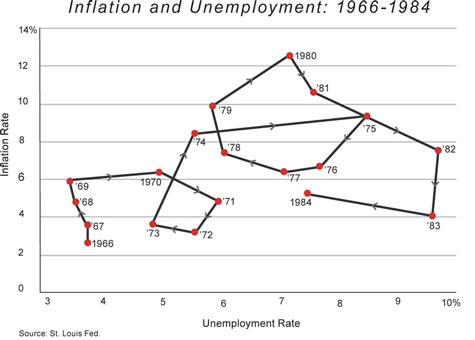

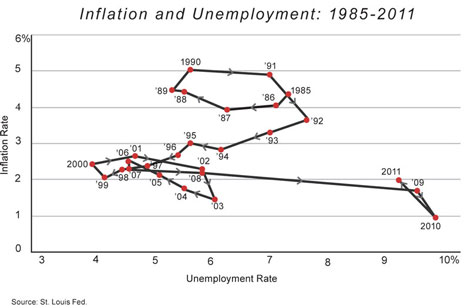

One serious problem with this view is that the correlation betwixt unemployment (or other measures of economic "slack") and inflation is actually very weak. The charts below show inflation and unemployment in the United states of america over the past several decades. If "slack" and "tightness" drove aggrandizement, we would meet a clear, negatively sloped line: College inflation would correspond to lower unemployment, and vice versa. Merely the charts show nearly no relation between aggrandizement and unemployment. From 1992 to 2001, inflation and unemployment declined simultaneously. More than alarming, from 1973 to 1975, and again from 1978 to 1981, inflation rose dramatically despite high and rising levels of unemployment and other measures of "slack."

This lack of correlation should not exist surprising. If inflation were associated only with booming economies, Zimbabwe — which experienced roughly 11,000,000% inflation in recent years — should exist the richest country on globe. If devaluing the currency yielded stimulus and improved competitiveness, and so Hellenic republic's many devaluations in the decades before it joined the euro should accept made it the envy of Europe, not its basket case.

Moreover, correlation is not causation. In the Fed'southward view, slack and tightness cause inflation and deflation. There is even less support for this view than for the thought that slack, or the lack thereof, can reliably forecast inflation.

Keynesians are aware of these difficulties, of course, and they have an reply: expectations. In essence, they fence that a boomlet can occur if the public can be surprised with inflation. If people are fooled into thinking higher prices are real, they'll piece of work harder. If people know inflation is coming, all the same, they volition just raise prices and wages without changing their economic plans or activities. There actually is a negatively sloped bend in the charts, they would argue, only an increment in expected inflation shifts the whole curve up. Since expectations are hard to measure independently, this view is difficult to disprove, but that also means it is hard to use for anything more than storytelling after the fact.

In this assay, the stagflations of 1973-75 and 1978-81 represented increases in expected inflation, while the turn down in inflation from the 1980s to 2000 — which occurred without substantial increases in unemployment — represented a Fed victory in disarming people that they should expect lower aggrandizement.

These views are evident in Fed chairman Ben Bernanke'south July thirteen testimony before the House Financial Services Committee:

Reasons to wait aggrandizement to moderate include the apparent stabilization in the prices of oil and other bolt, which is already showing through to retail gasoline and food prices; the all the same-substantial slack in U.South. labor and product markets, which has made it hard for workers to obtain wage gains and for firms to pass through their college costs; and the stability of longer-term aggrandizement expectations, every bit measured by surveys of households, the forecasts of professional private-sector economists, and financial market indicators.

To Bernanke, costs, slack, and expectations drive inflation — and not the coin supply, or the national debt. In this view, monitoring the "stability" of long-term expectations is vital, as is making sure that expectations stay "anchored." We exercise not want people to respond to little blips of inflation with a fear that long-term inflation is about to pause out.

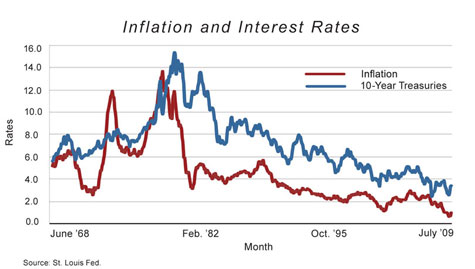

So how does the Fed know whether expectations are stable? The central bank's more than extensive reports mirror the logic of the quote above: They signal to surveys, forecasts, and low long-term interest rates. But the problem is that surveys, forecasts, and long-term interest rates did not anticipate the inflation of the 1970s. For example, the nautical chart below plots the interest rate on ten-year Treasury notes and the inflation rate over the past four decades. If long-term involvement rates offered reliable warnings of inflation, we would see the interest rates ascension before increases in aggrandizement. That does not happen. Plain "anchors" can get unstuck speedily, and aggrandizement can surprise the bond market every bit well as the Fed.

Therefore, to trust that stagflation will not break out, we need some understanding of why expectations might exist "anchored." As many academic economists and Fed officials see it, the "anchor" is a belief in the Fed's fundamental toughness and commitment to fighting inflation. Today, in this view, people believe that the Fed volition respond to whatever meaningful inflation by raising involvement rates much more chop-chop and dramatically than it did in the 1970s — no matter how high unemployment is, or how loudly Congress and the president scream that the Fed is throttling the economic system with tight coin, or how much the "credit constraint" and "save the banks" crowds insist that the Fed is killing the banking arrangement, or how many "temporary factors," "toll shocks," or other excuses analysts can come up with to explain away emerging inflation.

Expectations are even more key in the "New Keynesian" theories pop among academics and central-banking concern inquiry staffs effectually the world. These theories hold that the Fed's proclamation of its aggrandizement target should by itself exist enough to "coordinate expectations," and force the economy to jump to ane of many possible "multiple equilibria."

This line of academic theory is making its way into policy assay. For example, Imf main economist Olivier Blanchard recommended last year that the Fed induce some more inflation in order to stimulate the economy, and argued that, to exercise then, the Fed needed merely to announce a higher target. This view likewise helps to explain the Fed's growing commitment to communicating its intentions. For case, the Fed's major "stimulative" action over the summertime was its announcement that involvement rates would stay low for a long time in the future; it did not brand any physical policy movement.

This view is in many ways reminiscent of the "wage-price spiral" thinking of the 1940s, or fifty-fifty the "Whip Aggrandizement Now" buttons that Ford-administration officials used to habiliment on their lapels. If we merely talk about lower inflation, lower inflation will happen.

But are inflation expectations really "anchored" because anybody thinks the Fed is full of hawks who will raise rates dramatically at the showtime sign of inflation? Does the average person actually pay any attention to Fed promises and targets, so that inflation expectations will "coordinate" toward whatever the Fed wants them to be?

Still if neither a widespread belief in the Fed's toughness nor the "coordinating" action of the Fed's pronouncements is the fundamental to the stable expectations we take seen for the past 20 years, what does explain them? One plausible respond is reasonably sound fiscal policy, which is the central precondition for stable inflation. Major explosions of inflation around the world have ultimately resulted from fiscal problems, and it is hard to call up of a fiscally sound country that has ever experienced a major aggrandizement. And then long as the government's financial house is in order, people will naturally assume that the cardinal bank should exist able to stop a small uptick in inflation. Conversely, when the government'due south finances are in disarray, expectations can become "unanchored" very quickly. But this link between fiscal and monetary expectations is as well frequently unacknowledged in our conventional inflation debates — and information technology's non only the Keynesians who ignore information technology.

THE MONETARISTS' MISTRUST

For 50 years, monetarism has been the foremost alternative to Keynesianism as a means of understanding aggrandizement. Monetarists think inflation results from too much money chasing likewise few goods, rather than from involvement rates, demand, and the slack or tightness of markets.

Monetarists today accept plenty of reason to worry, as the money supply has been ballooning. Before the 2008 financial crisis, banks held most $l billion in required reserves and well-nigh $6 billion in excess reserves. (Reserves are accounts that banks hold at the Fed; they are the most important component of the money supply, and the i well-nigh directly controlled past the Fed.) Today, these reserves amount to $1.6 trillion. The monetary base, which includes these reserves plus cash, has more than doubled in the past three years equally a consequence of the Federal Reserve's attempts to answer to the financial crisis and recession.

Monetarists fright that such increases in the quantity of money portend aggrandizement of a similar magnitude. For example, in a 2009 Wall Street Journal op-ed, economist Arthur Laffer warned:

Get ready for inflation and higher interest rates . . . The unprecedented expansion of the money supply could make the '70s await benign . . . . We tin can expect quickly rise prices and much, much higher interest rates over the next four or 5 years . . . .

In an interview with the Wall Street Journal before this year, Philadelphia Fed president Charles Plosser issued a more muted (but similar) alert:

We accept all these excess reserves sitting in the banking arrangement, a trillion-plus backlog reserves . . . . As long as [the backlog reserves] are just sitting at that place, they are just the fuel for inflation, they are not really causing inflation . . . if they flow out too apace, we will potentially confront some serious inflationary pressures.

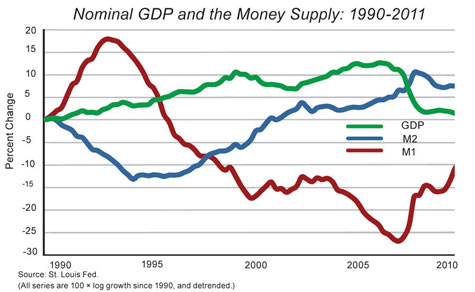

While I likewise worry nearly aggrandizement, I do not think that the money supply is the source of the danger. In fact, the correlation between inflation and the money stock is weak, at all-time. The chart below plots the 2 most common money-supply measures since 1990, forth with changes in nominal gross domestic production. (M1 consists of cash, bank reserves, and checking accounts. M2 includes savings accounts and money-marketplace accounts. Nominal Gdp is output at current prices, which therefore includes inflation.) As the nautical chart shows, money-stock measures are not well correlated with nominal Gross domestic product; they practise non forecast changes in inflation, either. The correlation is no better than the 1 betwixt unemployment and aggrandizement.

Why is the correlation between money and inflation so weak? The view that money drives inflation is fundamentally based on the supposition that the need for money is more or less constant. Just in fact, money demand varies greatly. During the contempo financial crunch and recession, people and companies all of a sudden wanted to hold much more cash and much less of whatever other asset. Thus the sharp rise in M1 and M2 seen in the chart is not best understood as showing that the Fed forced coin on an unwilling public. Rather, it shows people clamoring to the Fed to exchange their risky securities for coin and the Fed accommodating that demand.

Money demand rose for a second reason: Since the fiscal crisis, involvement rates have been essentially zero, and the Fed has likewise started paying involvement on depository financial institution reserves. If people and businesses tin can earn 10% past holding government bonds, they accommodate their diplomacy to hold picayune cash. Only if bonds earn the same equally greenbacks, it makes sense to keep a lot of cash or a loftier checking-business relationship residual, since cash offers bully liquidity and no financial cost. Fears well-nigh hoards of reserves nigh to be unleashed on the economy miss this basic bespeak, as exercise criticisms of businesses "unpatriotically" sitting on piles of cash. Correct at present, holding greenbacks makes sense.

Mod monetarists know this, of course. The older view that the demand for money is constant, and and so inflation inevitably follows money growth, is no longer normally held. Rather, today'south monetarists know that the huge need for money will presently subside, and they worry most whether the Federal Reserve will be able to adjust. Laffer continues:

. . . the panic demand for money has begun to and should continue to recede . . . . Reduced demand for coin combined with rapid growth in money is a surefire recipe for aggrandizement and college involvement rates.

Laffer's worry is merely that "rapid growth" in money will non cease when the "panic need" ceases. Plosser writes similarly

Some people have questioned whether the Federal Reserve has the tools to go out from its extraordinary positions. We exercise. Simply the question for the Fed and other central bankers is non can we do it, but will we exercise it at the right time and at the correct pace.

The Fed tin can instantly raise the interest charge per unit on reserves, thereby in effect turning reserves from "greenbacks" that pays no involvement to "overnight, floating-rate government debt." And the Fed notwithstanding has a huge portfolio of bonds it tin can quickly sell. Mod monetarists therefore concede that the Fed can undo monetary expansion and avoid inflation; they simply worry virtually whether it volition do then in time. This is an important business concern. But it is far removed from a belief that the astounding rise in the coin supply makes an equally astounding increase in aggrandizement only unavoidable.

And similar the Keynesians, the monetarists do not consider our deficits and debt when they call up about aggrandizement. Their formal theories, like the Keynesian ones, assume in footnotes that the regime is solvent, so there is never pressure for the Fed to monetize intractable deficits. But what if our huge debt and looming deficits hateful that the fiscal backing for monetary policy is almost to become unglued?

THE FISCAL OUTLOOK

Yous don't have to visit right-wing spider web sites to know that our fiscal situation is dire. The Congressional Budget Part's almanac Long-Term Budget Outlook is scary enough. Annual deficits are now running about $one.5 trillion, or 10% of GDP. Most half of all federal spending is borrowed. By the end of 2011, federal debt held past the public will be lxx% of GDP, and overall federal debt (which includes debt held in government trust funds) volition exist 100% of GDP. The CBO foresees a pass up in deficits accompanying its prediction of a strong economical recovery, but predicts that the debt held by the public will still ascension swiftly to 100% of Gross domestic product and beyond in but the coming decade. And then, as the Baby Boomers retire, health-intendance entitlements and Social Security obligations balloon, and debt and deficits explode. And the CBO is optimistic. In a recent paper aptly titled "Tempting Fate," Alan Auerbach (of the University of California, Berkeley) and Douglas Gale (of the Brookings Establishment) project "a long-term financial gap of betwixt five and 6 percent of GDP."

3 factors brand our state of affairs even more dangerous than these grim numbers suggest. First, the debt-to-GDP ratio is a misleading statistic. Many commentators tell us that ratios below 100% are safe, and note that we survived a 140% debt-to-Gdp ratio at the end of Earth War II. Merely there is no safe debt-to-Gross domestic product ratio. There is only a "condom" ratio between a state'southward debt and its ability to pay off that debt. If a country has strong growth, stable expenditures, a coherent taxation system, and solid expectations of time to come budget surpluses, it can borrow heavily. In 1947, everyone understood that war expenditures had been temporary, that huge deficits would finish, and that the The states had the power to pay off and grow out of its debt. None of these conditions holds today.

Second, official federal debt is only office of the story. Our government has made all sorts of "off balance sheet" promises. The government has guaranteed nigh $five trillion of mortgage-backed securities through Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The government conspicuously considers the big banks likewise important to fail, and will assume their debts should they get into trouble once more, just every bit Europe is already bailing its banks out of losses on Greek bets. State and local governments are in trouble, as are many government and private defined-benefit pensions. The federal government is unlikely to let them fail. Each of these commitments could all of a sudden dump massive new debts onto the federal Treasury, and could be the trigger for the kind of "run on the dollar" explained here.

Tertiary, future deficits resulting primarily from growing entitlements are at the heart of America's problem, not current debt resulting from past spending. We could pay off a 100% debt-to-Gdp ratio without aggrandizement, at least if we returned promptly to growth and didn't rack upwards a whole lot more debt first. But even if the United States eliminated all of its outstanding debt today, we would still face terrible projections of future deficits. In a sense, this fact puts u.s.a. in a worse situation than Ireland or Greece. Those countries have accumulated massive debts, simply they would exist in good shape (Republic of ireland) or at to the lowest degree a stable basket case (Greece) if they could wipe out their current debts. Not us.

Promised Medicare, alimony, and Social Security payments (known equally "unfunded liabilities") tin can be thought of every bit "debts" in the same mode that promised coupon payments on government bonds are debts. To get a sense of the telescopic of this problem, we tin can try to translate the forecasts of deficits in our entitlement programs to a present value. These estimates are rough, of class, but typical numbers are $60 trillion or more — swamping our $14 trillion of bodily federal debt.

The idea that these fiscal issues could lead to a debt crisis is hardly a radical insight. Equally even the circumspect Congressional Budget Part warned earlier this year:

. . . a growing level of federal debt would also increment the probability all of a sudden fiscal crunch, during which investors would lose conviction in the government'due south power to manage its upkeep, and the government would thereby lose its ability to borrow at affordable rates. It is possible that involvement rates would ascent gradually as investors' confidence declined, giving legislators accelerate alarm of the worsening state of affairs and sufficient time to make policy choices that could avert a crisis. Just as other countries' experiences testify, it is besides possible that investors would lose confidence abruptly and interest rates on government debt would ascent sharply. The exact indicate at which such a crunch might occur for the Us is unknown, in part because the ratio of federal debt to Gross domestic product is climbing into unfamiliar territory and in function considering the take chances of a crunch is influenced by a number of other factors, including the authorities'due south long-term budget outlook, its near-term borrowing needs, and the health of the economic system. When fiscal crises exercise occur, they often happen during an economic downturn, which amplifies the difficulties of adjusting financial policy in response.

Bernanke has been echoing this warning with a caste of bluntness very unusual for a Fed chairman. In testimony before the House Upkeep Committee earlier this year, he said:

The question is whether these [fiscal] adjustments will take place through a conscientious and deliberative process . . . or whether the needed fiscal adjustments volition come as a rapid and painful response to a looming or actual financial crisis . . . . if authorities debt and deficits were actually to abound at the step envisioned, the economic and financial effects would be astringent.

Neither the CBO nor Chairman Bernanke mentioned aggrandizement in these warnings. But precisely the situation they warn about carries a significant adventure of inflation amongst a weakening economy — an aggrandizement that the Fed could do little to control.

FISCAL Aggrandizement

To see why, start with a basic economic question: Why does paper money take any value at all? In our economic system, the bones answer is that it has value because the government accepts dollars, and but dollars, in payment of taxes. The butcher takes a dollar from his client because he needs dollars to pay his taxes. Or possibly he needs to pay the farmer, but the farmer takes a dollar from the butcher because he needs dollars to pay his taxes. As Adam Smith wrote in The Wealth of Nations, "A prince, who should enact that a sure proportion of his taxes should be paid in a paper money of a certain kind, might thereby give a certain value to this paper money."

Inflation results when the government prints more dollars than the government somewhen soaks upwardly in tax payments. If that happens, people collectively try to get rid of the extra cash. We try to buy things. But at that place is just so much to buy, and extra cash is like a hot potato — someone must always concur it. Therefore, in the end, we just push up prices and wages.

The authorities tin can also soak up dollars by selling bonds. It does this when it wants temporarily to spend more (giving out dollars) than information technology raises in taxes (soaking up dollars). But government bonds are themselves only a hope to pay back more than dollars in the hereafter. At some point, the government must soak upwards extra dollars (beyond what people are willing to agree to make transactions) with tax revenues greater than spending — that is, by running a surplus. If not, we get aggrandizement.

If people come to believe that bonds held today will exist paid off in the hereafter past printing money rather than by running surpluses, then a large debt and looming future deficits would take a chance time to come inflation. And this is what most observers assume. In fact, however, fears of future deficits can too cause inflation today.

The central reason is that our regime is now funded mostly past rolling over relatively short-term debt, not by selling long-term bonds that will come up due in some future time of projected budget surpluses. One-half of all currently outstanding debt volition mature in less than two and a half years, and a third will mature in under a year. Roughly speaking, the federal government each year must take on $6.5 trillion in new borrowing to pay off $5 trillion of maturing debt and $1.5 trillion or so in electric current deficits.

Every bit the government pays off maturing debt, the holders of that debt receive a lot of money. Ordinarily, that coin would be used to buy new debt. Simply if investors start to fear inflation, which volition erode the returns from authorities bonds, they won't buy the new debt. Instead, they volition try to buy stocks, existent estate, bolt, or other assets that are less sensitive to inflation. But there are simply so many real assets around, and someone has to hold the stock of coin and regime debt. So the prices of real assets volition rise. Then, with "paper" wealth high and prospective returns on these investments declining, people will offset spending more on goods and services. But at that place are only so many of those around, as well, so the overall price level must ascension. Thus, when curt-term debt must be rolled over, fears of future inflation give united states of america inflation today — and potentially quite a lot of aggrandizement.

It is worth looking at this process through the lens of present values. The real value of authorities debt must equal the present value of investors' expectations about the future surpluses that the government will somewhen run to pay off the debt. If investors recollect that these surpluses will be much lower — that government will either default or inflate away, say, one-half of their hereafter repayment — so the value of authorities debt will be only $vii trillion today, non $14 trillion. Bail holders will therefore try to sell off their debt before its value falls.

If merely long-term debt were outstanding, these investors could try to sell long-term debt and buy short-term debt. The cost of long-term debt could fall by one-half (thus long-term involvement rates would ascension) so that the value of the debt would once over again be the present value of expected surpluses. But if only curt-term debt is outstanding, investors must try to buy appurtenances and services when they sell government debt. The only fashion to cutting the real value of government debt in one-half in this situation is for the price level to double.

In a sense, this confirms the Keynesians' view that expectations matter, but not their view of what the sources of those expectations are. A fiscal inflation would happen today because people expect inflation in the future. A "loss of anchoring," to employ a Keynesian term, would thus likely to lead to stagflation rather than to a boomlet of growth.

The Treasury probably borrows using short-term bonds considering brusque-term involvement rates are lower than long-term rates. The regime thus thinks it'southward saving us coin. But long-term rates are higher for a reason: Long-term debt includes insurance against crises. It forces bondholders to bear risks otherwise borne by the government and, ultimately, by taxpayers and users of dollars. Like all insurance, a premium that seems onerous if there is no disaster tin seem in retrospect to have been remarkably small if in that location is one. And, unfortunately, the very fact that and so much of our debt is short term makes such a disaster more than likely.

INFLATION AND INTEREST RATES

Interest rates are very depression, just they are likely to rising. An increase in interest rates could also bring on aggrandizement today, compounding the inflationary outcome of a potential debt crunch through a very like mechanism.

Just how depression are today'south rates? The ane-twelvemonth rate is at present 0.2%; the ten-year rate is about 2%, and the xxx-yr rate is only four%. We have non seen rates this low in the postal service-state of war era. Furthermore, inflation is withal running at around 2-3%, depending on exactly what measure of inflation we choose. If an investor lends money at 0.2% and inflation is two%, he loses one.8% of the value of his coin every year. Such low rates are therefore unlikely to last. Sooner or later, people volition detect better things to practise with their money, and demand college returns to hold Treasury debt.

Low interest rates are partially a result of the Fed's deliberate efforts. During the past year's $600 billion "quantitative easing," the Fed essentially bought near a third of the Treasury's bail issues, in an try to raise bond prices and thereby lower interest rates. Just both the Fed'southward want to keep rates this low and its ability to practice and then are surely temporary.

Low involvement rates are also partly a reflection of investors' "flight to quality," as they have sought shelter in American debt amidst the fiscal crunch and the emerging European debt crisis. U.South. debt has long been perceived as the ultimate safe harbor: Investors believe that the United States volition never default or miss an involvement payment, and that surprise inflation could not eat away much of the real value of short-term debt in a twelvemonth. Short-term U.S. debt is also very liquid, meaning it is easy to sell and easy to borrow against. People are willing to hold it despite low involvement rates for much the same reason they are willing to hold coin despite no interest rate.

Just this special status, also, could modify. It became clear during this past summer's debt-limit negotiations that the federal government is less committed to paying interest on its debt than many observers had idea. For example, in a July breakfast with Bloomberg reporters, President Obama'south chief political advisor, David Plouffe, said on the record that "the notion that nosotros would only pay Wall Street bondholders and the Chinese government and not meet our Social Security and veterans' obligations is insanity, and is not going to happen." No administration official or congressional pronouncement has corrected or contradicted this astonishing statement. Missing interest payments would instantly mean a loss of liquidity of U.South. debt, even if the long-run budget were non an issue — which of grade information technology very much is. The S&P ratings downgrade is only the get-go warning sign.

A "normal" real interest charge per unit on government debt is at to the lowest degree ane-2%, pregnant a 4-v% one-yr rate even if inflation stays at 2-3%. A loss of the special safety and liquidity disbelieve that American debt now enjoys could add together ii to three percent points. A rising risk premium would imply higher rates yet. And of form, if markets started to expect aggrandizement or bodily default, rates could rise even more than. Depression interest rates can climb quickly and unexpectedly, as Greece and Espana have learned.

A rising in interest rates can atomic number 82 to electric current aggrandizement in the same mode a change in investor views nearly long-term deficits can. Every per centum point that involvement rates ascension ways, roughly, that the U.Due south. authorities must pay $140 billion more than per year on $xiv trillion of debt, thus directly raising the arrears by about 10%. If we revert to a normal 5% interest rate, this means about $800 billion in extra financing costs per year — about half again the contempo (and already "unsustainable") annual deficits. And this number is cumulative, as larger deficits mean more and more than outstanding debt.

Once again, present values tin can help analyze the point. The rate of return that investors need in substitution for lending money to the government is just equally important to the present value of hereafter surpluses as is the amount of future surpluses that investors await. If investors decided they were no longer happy to earn ane% (let alone -1%) in existent terms when lending to the government, then the real value of debt today would take to autumn just every bit if investors decided that the authorities would inflate or default on part of the debt. And since and then much debt is short term, a fall in the real value of the debt must button the price level up.

These two factors — expectations of future surpluses and deficits, and increases in interest rates — are likely to reinforce each other. If bond investors decide that the government is likely to inflate or default on office of the debt, investors are likely to simultaneously need a higher risk premium to hold the debt. The two forces will combine to apply even greater pressure toward inflation.

A RUN ON THE DOLLAR

These dynamics essentially add up to a "run" on the dollar — just similar a bank run — away from American government debt. Unlike a bank run, even so, it would play out in slow motion.

Before the financial crisis, Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers rolled over debt every twenty-four hour period in order to invest in mortgage-backed securities and other long-term illiquid assets. Each day, they had to borrow new coin to pay back the one-time money. When the marketplace lost faith in the long-term value of their investments, the market refused to coil over the loans, and the ii companies failed instantly.

The U.s.a. rolls over its debt on a scale of a few years, not every day. So the "run on the dollar" would play out over a year or two rather than overnight. Furthermore, I have described for clarity a sudden one-time loss of confidence. The bodily process of running from the dollar, withal, is likely to accept more time, much as the European debt crisis has trundled along for more than a year. In addition, because prices tend to change relatively slowly, measured inflation tin take a year or ii to build up afterward a debt crisis.

Similar all runs, this one would be unpredictable. After all, if people could predict that a run would happen tomorrow, then they would run today. Investors do not run when they come across very bad news, but when they get the sense that everyone else is nigh to run. That's why at that place is ofttimes so piffling news sparking a crisis, why policymakers are probable to blame "speculators" or "contagion," why bookish commentators blame "irrational" markets and "beast spirits," and why the Fed is likely to bemoan a mysterious "loss of anchoring" of "aggrandizement expectations."

For that reason, I do not claim to predict that inflation will happen, or when. This scenario is a warning, not a forecast. Extraordinarily low interest rates on long-term U.S. government bonds propose that the overall marketplace still has organized religion that the United States will figure out how to solve its issues. If markets interpreted the CBO's projections equally a forecast, not a warning, a run would have already happened. And our debt and deficit problems are relatively like shooting fish in a barrel to solve as a matter of economics (if less so of politics).

Only nosotros are primed for this sort of run. All sides in the current political fence describe our long-term financial trajectory every bit "unsustainable." Major market players such equally Pimco — which manages the earth's largest mutual fund — are publicly announcing that they are getting out of U.S. Treasuries and even shorting them, as major players similar Goldman Sachs famously shorted mortgage-backed securities before that crash.

As with all runs, once a run on the dollar began, it would be too late to stop it. Confidence lost is difficult to regain. Information technology is not plenty to convince this yr's borrowers that the long-term budget problem is solved; they take to be convinced that next year'southward borrowers volition believe the same thing. It would be far better to find ways to avert such a crisis than to be left searching for ways to recover from it.

THE IMPOTENT Cardinal Bank

The Fed is noticeably absent-minded from this terrifying scenario. We have come to think that primal banks command aggrandizement. In fact, the Fed'south ability to control inflation is limited — and the depository financial institution would exist especially impotent in the event of fiscal or "run on the dollar" inflation.

The Fed's main policy tool is an "open-marketplace operation": It can buy authorities bonds in return for cash, or it can sell authorities bonds to soak upwardly some money. Thus, the Fed can alter the composition of regime debt, simply not the overall quantity. Money, after all, is just a different kind of government debt, one that happens to come in minor denominations and doesn't pay interest. Bank reserves, which now pay interest, are just very liquid, 1-solar day maturity, floating-rate debt. So the Fed tin affect financial affairs and ultimately the toll level only when people care near the kind of government debt they hold — reserves or cash versus Treasury bills.

But in the "run from the dollar" scenario, people want to get rid of all forms of government debt, including coin. In that state of affairs, there is essentially nothing the Fed can do. When at that place is as well much debt overall, changing its composition doesn't really thing.

The Fed is particularly powerless at present, equally short-term interest rates are essentially zero, and banks are property $i.5 trillion of backlog reserves. In this situation, coin and short-term government debt are exactly the aforementioned thing. Monetary policy today is like taking away a person's cherry-red M&Ms, giving him greenish M&Ms, and expecting the change to affect his diet.

How can the Fed be powerless? Milton Friedman said that the government can always cause aggrandizement past essentially dropping coin from helicopters. That seems sensible. But the Fed cannot, legally, drop money from helicopters. The Fed must always take back a dollar'due south worth of government debt for every dollar of greenbacks it bug, and the Fed must give back a government bond for every dollar information technology removes from circulation. While it is easy to imagine that giving everyone a newly printed $100 bill might crusade inflation, it is much less obvious that giving everyone that neb and simultaneously taking away $100 of everyone'due south government bonds has whatever effect.

There is a good reason why the Fed is non immune this near effective tool of cost-level control. Writing people checks (our equivalent of dumping money from helicopters) is a fiscal performance; it counts as authorities spending. The reverse is taxation. In a democracy, an contained institution like a central banking concern cannot write checks to voters and businesses, and it cannot impose taxes.

Moreover, the Fed's ability to control inflation is e'er conditioned on the Treasury's ability and willingness to validate the Fed's actions. If the Fed wants to ho-hum down inflation by raising interest rates, the Treasury must raise the additional revenue needed to pay off the consequently larger payments on government debt. For case, in the 1980s, the lowering of inflation patently induced by monetary tightening was successful (while attempts to do the same in Latin America failed) but because the U.South. government did in fact repay bondholders at higher rates. Monetary theories in which the Fed controls the price level, including the Keynesian and monetarist views sketched to a higher place, always presume this "budgetary-financial policy coordination." The issue we face up is that this assumed fiscal rest may evaporate. The Treasury may simply not produce the needed revenue to validate monetary policy. In that instance, the Federal Reserve would non be the central player. Standard theories fail because one of their central assumptions fails. Again, events outpace ideas.

Ane might imagine a resolute central bank trying to finish fiscal aggrandizement by saying, "Nosotros will not monetize the debt, ever. Permit the rest of the government slash spending, raise taxes, or default." In that case, people might flee authorities debt, seeing default coming, but they would not flee the currency considering they would not run into inflation coming.

Simply such behavior by our Federal Reserve seems unlikely. Imagine how the "run on the dollar" or "debt crunch" would feel to cardinal-bank officials. They would come across interest rates spiking, and Treasury auctions failing. They would see "illiquidity," "market place dislocations," "market partition," "speculation," and "panic" in the air — all terms used to describe the 2008 crisis equally it happened. The Fed doubled its balance sheet in that fiscal crunch, issuing money to buy assets. It bought $600 billion more than of long-term debt in 2010 and 2011 in the hope of lowering interest rates past ii-tenths of a percentage point. It would be amazing if the Fed did not "provide liquidity" and "stabilize markets" with massive purchases in a authorities-debt crisis.

We may get a preview of this scenario courtesy of Europe, where the European Cardinal Banking concern — responding to similar pressures — is already buying Greek, Portuguese, and Irish debt. The ECB is as well lending vast amounts to banks whose main investments and collateral consist of these countries' debts. If a large sovereign-debt default were to happen, the ECB would not have assets left to buy back euros. As in the scenario described above in the context of the dollar, a "run" on the euro could thus atomic number 82 to unstoppable inflation.

Neither the cause of nor the solution to a run on the dollar, and its consequent inflation, would therefore be a affair of monetary policy that the Fed could do much about. Our problem is a fiscal problem — the challenge of out-of-control deficits and ballooning debt. Today'south debate about aggrandizement largely misses that problem, and therefore fails to argue with the greatest aggrandizement danger we face.

AVOIDING THE CRISIS

An American debt crunch and consequent stagflation do non have to happen. The solution is simple as a matter of economics. This is why all of the various financial and upkeep commissions of the by few years, regardless of which party has appointed them, have come up upwards with the same basic answers.

Our largest long-term spending problem is uncontrolled entitlements. Our entitlement programs crave fundamental structural reforms, not merely promises to anytime spend less money under the current arrangement. Congressman Paul Ryan's programme to essentially turn Medicare into a arrangement of vouchers for the buy of private insurance is an example of the old. The annually postponed "doc fix" promise to slash Medicare reimbursement rates is an example of the latter. Ryan and the Obama administration actually project spending about the aforementioned amount of coin on Medicare in the long run; the difference is that the bail markets are much more likely to be convinced by a structural change than a spreadsheet of promises.

Above all, nosotros need to render to long-term growth. Tax revenue is equal to the tax rate multiplied past income, so there is nothing like more income to enhance government revenues. And small changes in growth rates imply dramatic changes in income when they compound over a few decades. Conversely, a consensus that we are inbound a lost decade of no or low growth could be the disastrous budget news that pushes us to a crisis.

Much of the current policy fence focuses on boosting GDP for just a twelvemonth or two — the sort of matter that might (perhaps) be influenced by "stimulus" or other short-term programs. But non fifty-fifty in the wildest Keynesian imagination do such policies produce growth over decades.

Over decades, growth comes just from more people and more productivity — more output per person. Productivity growth fundamentally comes from new ideas and their implementation in new products, businesses, and processes. This fact ought to give the states comfort: We are still developing and applying reckoner and internet technology like mad, and biotechnology and other innovative fields have only begun to bear fruit. We are still an innovative land in an innovative global economy. We have non run out of ideas. But governments have a great capacity to terminate or irksome downwardly growth. Witness Greece. Witness Cuba.

Our taxation rates are besides high and revenues are as well low. We should aim for a system that does roughly the reverse — raising the necessary tax revenue with the lowest possible revenue enhancement rates, especially in those areas in which high rates create disincentives to work, save, invest, and contribute to economical growth. The disincentives implied by college tax rates may not evidence upwards for a year or two, as it takes time to discourage growth. Simply when small effects cumulate over decades, they have particularly pernicious effects on growth.

Regulatory and legal roadblocks can be even more than damaging to growth than high taxation rates, revenue enhancement expenditures, and spending. The uncertain threat of a visit from the Environmental Protection Agency, National Labor Relations Lath, Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, Securities and Exchange Commission, or the new Consumer Financial Protection Bureau can be a greater disincentive to hiring people and investing in a concern than a unproblematic and calculable tax.

We stand at the brink of disaster. Today, we face up the possibility of a debt crisis, with the consequent financial anarchy and aggrandizement, that the Fed cannot control. In gild to address this danger, we take to focus on its true nature and causes. The electric current inflation fence, focused on tinkering with interest rates and Fed announcements, completely misses the marking. Our desire to avoid a dangerous inflation should point us in the same direction every bit just well-nigh every other economic indicator and business organization: It should point us toward finally bringing our deficits and debt under command and spurring long-term growth.

Source: https://www.nationalaffairs.com/publications/detail/inflation-and-debt

0 Response to "Surprise Inflation Can Help People Who Borrow Money."

Post a Comment